Tags

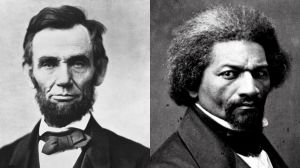

One of the many books on my shelves is The Radical and the Republican, by James Oakes. It discusses the roles played by abolitionist, Frederick Douglass, and the first Republican President, Abraham Lincoln. The book got me thinking about the most effective ways to initiate change.

One of the many books on my shelves is The Radical and the Republican, by James Oakes. It discusses the roles played by abolitionist, Frederick Douglass, and the first Republican President, Abraham Lincoln. The book got me thinking about the most effective ways to initiate change.

As a former slave, Douglass felt an urgency to end slavery, and now. He actively and emphatically pressed his case to anyone who would listen, and many who wouldn’t. As Lincoln was emerging as a viable voice against slavery, Douglass thought the man too timid, unwilling to take a stand for black rights. Ever the moderate, Lincoln focused solely on blocking the extension of slavery into the territories, feeling the U.S. Constitution protected slavery where it already existed, mainly the South. Lincoln did advocate for gradual, compensated, voluntary emancipation, but also that ex-slaves would be better off if they colonized their own countries in Africa and the Caribbean.

Two men with inherently different perspectives and beliefs, yet eventually, the two would work separately and together to accomplish the same goal – emancipation. They became mutually respecting friends.

Today we have many issues that seem too difficult to resolve. And yet, for example, marriage equality, which seemed an impossible goal just a few years ago, is now the law of the land. Climate change is not only an American issue but a global one, and while it seems an insurmountable challenge, we’ve seen tremendous steps being taken on unilateral, bilateral, multilateral, and global levels.

How did these sweeping changes occur? In many ways, there are radicals and there are the politicians (which, in this age, are now mostly Democrats). LGBT rights activists, as had Frederick Douglass, maintained high visibility for the issue. They used media, grass roots demonstrations, and aggressive lobbying to raise awareness of discrimination. Like slavery, this went on for many decades with little apparent change effected. More moderate forces working within our legislative structures slowly sought incremental steps. Over time, public sentiment evolved enough for key political leaders like President Obama to have enough breathing room to publicly offer support. And then change happened, seemingly overnight.

Critically, there is the often agonizingly slow drift of public sentiment. Lincoln once noted:

In this and like communities, public sentiment is everything. With public sentiment, nothing can fail; without it nothing can succeed. Consequently he who molds public sentiment, goes deeper than he who enacts statutes or pronounces decisions. He makes statutes and decisions possible or impossible to be executed.

So it seems there are important roles for both radicals and political players in reading, and molding, public opinion. One keeps the high-pitch of awareness in the public eye; the other works the levers of legislative debate to find incremental compromise. Over time, the interplay between the two impacts public perception. When the public begins to accept the concept of change, in the sense that they no longer feel a threat to their own self interest, then change is allowed to happen. Often this happens quickly, as if a threshold is reached. The Sisyphean labor moves the boulder up the hill until, despite repeated setbacks, the crest is reached and it rolls into the future rather than the past.

Change is hard. Inertia keeps a body at rest in that inactive state until sufficient energy is applied to cause movement. But inertia also describes the state where motion remains in motion until something causes it to stop. There are always those who cause friction, that resist change; there remain today people who believe slavery was a merely “states rights” issue and not morally wrong. This means that once change occurs there will be continual struggle to maintain the benefit of that change. Just ask the LGBT and climate change action communities who must fight against reversals by bigoted and political forces.

To once again quote Abraham Lincoln: “I am a slow walker, but I never walk backward.”

Forward!

David J. Kent is a science traveler and the author of Lincoln: The Man Who Saved America, in Barnes and Noble stores now. His previous books include Tesla: The Wizard of Electricity (2013) and Edison: The Inventor of the Modern World (2016) and two e-books: Nikola Tesla: Renewable Energy Ahead of Its Time and Abraham Lincoln and Nikola Tesla: Connected by Fate.

Check out my Goodreads author page. While you’re at it, “Like” my Facebook author page for more updates!

History is always on the side of progress.

LikeLiked by 1 person

True, despite some folks disagreeing on what constitutes “progress.”

LikeLiked by 2 people

very nice!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article, and so very true. Political inertia is a funny thing in that regard. Like a pendulum, it seems a great deal of potential builds in those protracted intervals when there is so little movement. But there inevitably follow times of sweeping change. It’s probably human nature to resist, and consequently to move with determination only in moments of crisis. But eventually the gravity of reality always pulls us back to a center — for a moment anyway. A punctuated equilibrium of sorts.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. I feel like it could be something to flesh out more into an essay, though I doubt I’ll have the time/inclination to do so anytime soon. Punctuated equilibrium, seismic fault slippage, probably other good analogies.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great post I share the same sentiments. Check out my page for my current and upcoming political and theological posts. Follow for follow!

LikeLike

Thanks. Will check out your page. I’m hoping to expand on my thoughts above.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Throwback – lethe

Just a historical note: Mr. Lincoln’s emancipation affected only the slaves in the states that had already seceded from the Union. It did not apply to states above the Mason-Dixon Line. The struggle for complete abolition did not end with the Emancipation Proclamation, but it certainly got a huge boost. While I have great respect for Mr. Lincoln, it is important to remember that he, too, was a politician.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Indeed, the Emancipation Proclamation was a war-time tool to swing the advantage toward the North. It was just one of many actions that led to full emancipation, including the 13th amendment that Lincoln worked so hard for before being assassinated, as well as the 14th and 15th amendments and all the way through to the 1965 and 66 Civil and Voting Rights Acts. As we’ve seen in these most recent years, discrimination and racism continues today.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The heart of mankind continues today.

I was at a wedding over the weekend, and I was delighted to sit back and watch people–one of my favorite things. There was a mixture of Asian, Hispanic, Black, mixed-race, white; I was intrigued and so pleased to see them all comfortable together, laughing and talking. Some of them even broke out a game of Scrabble while we waited for the meal.

That’s the way it should be.

LikeLiked by 1 person